When you go to a new country, you want to try new and interesting foods, right? Japan has an endless variety of food and while you are studying Japanese, it can be an interesting way to learn bits and pieces of Japanese culture. Japan has a very rich food culture that both stays true to it’s roots and embraces endless variety of foreign and fusion styles. In this series, I’ll talk about the eating and drinking aspects of Japanese culture.

The Meal

The most important thing to understand about food in Japan is that the concept of a meal is very different in Japan. A meal is supposed to have some sort of meat, some sort of vegetable and either bread, noodles or rice. Subtract one from the mix and it may not be considered a meal for some. I’ve seen Japanese eat endless amount of vegetables and meat and still claim to be hungry because there is no rice, but as long as they have all three, they seem to be satisfied whether it’s portion made for a monster or for a mouse. The main dish is considered to be the rice, bread or noodle part. Everything else is side dishes, even if it’s the smallest part and even if you are anticipating it the least. The nice thing about this is that most things come in sets and you can find some really cheap lunch specials.

The one time this “main dish” rule does not apply is when drinking with co-workers or friends in a party like setting (and these settings are very common in Japan). At izakaya (or a cross between a restaurant and a bar with private seating), people forget the rules of balance and often beer becomes their starch of choice while they slowly eat all kinds of side dishes and share everything.

Drinks

Ordering a drink is almost understood at a Japanese. Of course no waiter or chef will get angry with you if you don’t drink alcohol but since food is often set at very fair prices, a lot of places make their money from drinks so depending on the price of the meal, at a local place, you may want to consider ordering at least an ice tea or coffee to keep the place running. The soft drinks are often close in price to the alcohol so some people find themselves drinking a lot more alcohol, trying to get more bang for their buck. I am certainly guilty of this. I usually check the atmosphere first to see if I can get away with not ordering a drink. If everyone around me is drunk or in a group or if the food is dirt cheap, I take it as a cue to get a drink. If it’s all families or if the dishes seem priced to make a profit, I skip the drink. Since I live in cafe’s, I am often ordering a drink though. We’ll talk all about drinking culture and the Izakaya in a future article.

Portions

There is a common complaint among some foreigners that portions are too small in Japan. I think this is a matter of expectations and if you don’t compare it to your own country, you may find yourself quite satisfied with the portions. Remember, it is considered polite to finish your entire meal and a chef may even feel a little pinch of sadness when someone doesn’t, although you should never force yourself. It is also very uncommon to take leftovers back with you may even get a confused look if you ask. In contrast, in the States or on trips to China, I find many people leaving a good portion of their meal for the garbage can.

As you study Japanese, don’t forget to enjoy the culture in one of the most fundamental and primitive ways possible: eating.

The task of choosing where to eat out (gaishoku, がいしょく, 外食) in Japan can be a difficult one. Upon venturing out to a busy area in the evening in Japan, you will be met by a dazzling array of neon, endless signs for eateries, often from basement up to the seventh or eighth floor or above and stretching off into the distance in all directions, with menu-bearing touts (yobikomi, よびこみ, 呼び込み) intent on herding potential customers in the direction of their particular restaurant. How can you navigate through this to a meal that fits both your palate and your wallet?

Low-budget Eateries

For the frugal, there are three donburi (どんぶり, 丼) chains that you cannot fail to come across in Japan. At these establishments, open 24 hours a day, you can buy a filling meal starting at just 250 or 290 yen, generally variants of bowls of rice covered with beef and vegetables (gyuudon, ぎゅうどん, 牛丼), although other options such as eel (unagi, うなぎ, 鰻) are also available. Selection of a dish and payment are often made via a machine, sometimes situated outside the restaurant to save space, so even foreigners with no spoken Japanese can order if they can read the text on the buttons, or try ‘pot luck’ and press a random button to select their meal.

Another option besides the donburi chains is yatai (やたい, 屋台), small food stalls with a few stools for customers. Ramen noodles are often the dish of choice at these places, and they are great in winter to warm you via both the food and being huddled around the stove/cauldron where the food is prepared. Alternatively, octopus balls (takoyaki, たこやき, たこ焼き) are a quick and tasty dish served at yatai that is particularly prevalent in Osaka.

Regular restaurants

A step up from the Japanese fast food options above is the izakaya (いざかや, 居酒屋). For an authentic Japanese eating experience, these are hard to beat. Often referred to as a Japanese pub, this translation really fails to do it justice. There are certainly similarities in the way that you will be greeted upon entering and leaving, the crowded seating arrangements that encourage interaction between tables and groups, and the ready flow of beer and other alcoholic beverages.

However, food takes a far more central stage in an system in which you eat or drink, respectively, as much as you like in a 60-, 90-, or 120-minute period for a set fee.

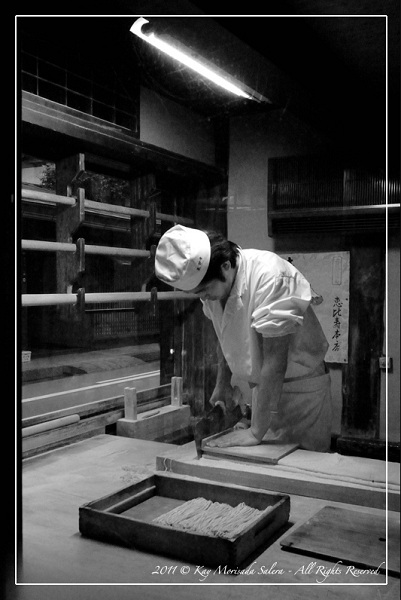

Besides the izakaya, there are a number of other middle-range restaurant options, at which, in contrast to the izakaya, the specific type of food available is reflected in the name of the category. Restaurants can specialize in food items such as yakitori (skewered chicken; やきとり, 焼き鳥), okinamiyaki (Japanese omelette/pancake; おこのみやき, お好み焼き), monja (pan-fried batter; もんじゃ), tempura (battered seafood or vegetables; てんぷら, 天ぷら), shabu shabu (Japanese hot-pot; しゃぶしゃぶ), and noodle dishes such as udon (うどん), soba (そば), ramen (らめん), and reimen (れいめん, 冷麺). Of course, sashimi (さしみ, 刺身) and sushi (すし, 寿司) are also always available. One particularly enjoyable option is the kaitensushi (rolling sushi; かいてんすし, 回転すし) , where the dishes pass by you on a conveyor belt, and the bill is determined by the number and colors of the various dishes that you are left with at the end of your meal (again not requiring too many Japanese language skills).

Foreign options

Despite the huge variety available within the category of Japanese food, you may sometimes hanker after something from outside the country. One budget option is Japanese curry, such as curry rice (kare-raisu, カレーライス), a hugely popular and somewhat watered down version of the traditional Indian dish. Alternatively, Korean food is a widely available option, which includes kimuchi (spicy Korean cabbage; キムチ), chijimi (Korean pancake; チジミ), and yakiniku restaurants (Korean barbecue; やきにく, 焼肉), at which you can grill food just like a barbecue at your own table. Such restaurants should be sought out in the Korean districts of the major cities, such as Shin-Okubo (しんおおくぼ, 新大久保) in Tokyo and Tsuruhashi (つるはし, 鶴橋) in Osaka, where the alleys around the station are clouded with the smoke of grilled beef. Any gourmet will really be spoilt for choice in terms of food in Japan.