The holiday お盆 is one of the most important holidays in Japan. It is also a time for people to return back to their families and home towns.

Obon and the purpose of obon

Obon, also known as Bon Festival, is a Japanese Buddhist tradition held to honor the spirits of one’s ancestors. Typically occurring in mid-August, the festival spans three days and includes various customs and rituals. The purpose of Obon is to reunite with and remember deceased family members, reflecting on their lives and expressing gratitude for their contributions.

During Obon, it is believed that ancestral spirits return to the physical world to visit their relatives. Families prepare by cleaning graves, offering food, and performing dances known as Bon Odori. Lanterns are lit to guide the spirits home, and at the festival’s end, floating lanterns are set adrift to guide the spirits back to the afterlife.

The word お盆 is often translated as “Bon festival”, but personally I feel that’s not really suitable. Anyway, you can decide for yourself after reading this article.

National Holiday for Most People

お盆 is one of the biggest customs here in Japan, and perhaps the only event regarding 仏教 (ぶっきょう – bukkyou – Buddhism) which involves taking time off from work. Interestingly enough, our 祝日 (しゅくじつ – shukujitsu – national holidays) aren’t related with 宗教 (しゅうきょう – shuukyou – religion), and お盆 isn’t a holiday, either. However, in most cases, lots of people can take days off for お盆, and actually public places such as 市役所(しやくしょ – shiyakusho – government offices), 郵便局 (ゆうびんきょく – yuubinkyoku – post offices), 病院 (びょういん – byouin – hospitals) are closed during obon days. Mostly お盆 is held during three days (13th – 15th) in August, or July in some regions.

Return of the Dead Spirits

Return of the Dead Spirits

In 仏教 (Buddhism), 魂 (たましい – tamashii – soul/spirit) of dead person comes back home on お盆, and we prepare to welcome it. Such a 魂 (soul/spirit– but we regard it as the “person” rather than his/her soul, I feel) is supposed to return to the tomb and to the house where the “person” was living when he/she died. So, we should clean these places.

We go to the 寺 (てら – tera – temple) which has the 墓 (はか – haka – grave or tomb) of our family, and clean the 墓 (tomb). After cleaning, we offer flowers and food like fruits and sweets at the 墓 (tomb). You might say something to the “person”, or talk about the “person” with your family and relatives in front of the 墓 (tomb).

After that, we enter the 寺 (temple). During お盆, lots of people visit there, and the 僧侶 (そうりょ – souryo – priest) recites a お経 (おきょう – okyou – sutra) for the soul/spirit. During the recitation of the お経 (sutra), people listen to it, or some of them might read in low voice together with the priest (some people have the sutra printed in a booklet). If you like music, you might find the traditional instruments which are played during the recitation interesting. Also, the 僧侶 (priest) often sings quite nicely. The 僧侶 (priest) for our family has a very nice voice, and I enjoy the music played along with the お経 (sutra) by the priests.

After that, we have to listen to a boring sermon by the 僧侶 (priest). Oops, I don’t mean to say that ALL priests give boring sermons, but at least they’re long and boring for children, and the parents have to watch them carefully, or they may start running around, lol.

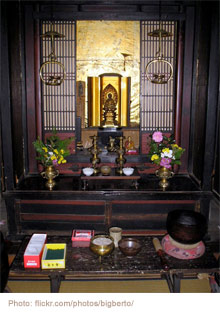

An Altar at Home

Well, when someone dies at home, you might purchase a 仏壇 (ぶつだん – butsudan – altar). It’s bigger (and expensive), so you might be not able to buy it if you’re living in a small appartment. Anyway, you clean the 仏壇 (altar) and place flowers and food on it as an offering. Even though you don’t clean the 仏壇 (altar) every day, you must do it during お盆 because more people are expected to visit then. Possibly you might prepare less offering because your relatives bring something probably; a box of sweets, or a basket of fruits and other food. Smaller things are welcome because we are supposed to eat them later or take them back home with us. A photo of the “person” is put on the 仏壇 (altar), and a child might ask to eat the “person’s” food offering as he/she wants to eat immediately, lol.

Well, when someone dies at home, you might purchase a 仏壇 (ぶつだん – butsudan – altar). It’s bigger (and expensive), so you might be not able to buy it if you’re living in a small appartment. Anyway, you clean the 仏壇 (altar) and place flowers and food on it as an offering. Even though you don’t clean the 仏壇 (altar) every day, you must do it during お盆 because more people are expected to visit then. Possibly you might prepare less offering because your relatives bring something probably; a box of sweets, or a basket of fruits and other food. Smaller things are welcome because we are supposed to eat them later or take them back home with us. A photo of the “person” is put on the 仏壇 (altar), and a child might ask to eat the “person’s” food offering as he/she wants to eat immediately, lol.

Well, this event is certainly related to 宗教 (religion), but actually we enjoy お盆 for several reasons; we can take some 休み (やすみ – yasumi – days off), meet with 親戚 (しんせき – shinseki – relatives) and enjoy talking about lots of things, including the “person”. Possibly you might not go to the 寺 (temple), or not even meet with your relatives. Some people only visit the 墓 (tomb), and they might talk to the “person” quietly. Regardless of how you spend お盆, perhaps you think of someone, and that will make the “person” happy.

Dancing the ぼんおどり

You might be looking forward to 盆踊り (ぼんおどり – bon-odori – bon dance). In some larger spaces such as 公園 (こうえん - kouen – park) and グランド (gurando – grounds) of a school, people start to prepare 盆踊り. If you hear 盆踊り music from the window of your room in the evening, you may try to go outside so that you can see children starting to dance. Some of the girls wear 浴衣 (ゆかた – yukata – kimono for summer) and 下駄 (げた – geta – Japanese wooden sandals). Such girls look so pretty and cute. The background music is for children, and sometimes each is given a bag of sweets or snacks after dancing.

After the children’s version, the real (?) 盆踊り starts. Naturally it becomes dark outside, so the place is illuminated by lots of small lights or 提灯 (ちょうちん – chouchin – paper lanterns). People dance slowly around a 櫓 (やぐら – yagura – high wooden stage), and some people are on the stage for the dance. Possibly the empty 櫓 (the high wooden stage) only has a CD or cassette player to play the music for 盆踊り, but you can find a real 太鼓 (たいこ – taiko – drum) player and one or more singers on the stage. Anyone can participate in the dance circle, but you can enjoy just watching the dance as well. Lots of people often return to their home towns during お盆, so you may run into some old friends at the 盆踊り place.

After the children’s version, the real (?) 盆踊り starts. Naturally it becomes dark outside, so the place is illuminated by lots of small lights or 提灯 (ちょうちん – chouchin – paper lanterns). People dance slowly around a 櫓 (やぐら – yagura – high wooden stage), and some people are on the stage for the dance. Possibly the empty 櫓 (the high wooden stage) only has a CD or cassette player to play the music for 盆踊り, but you can find a real 太鼓 (たいこ – taiko – drum) player and one or more singers on the stage. Anyone can participate in the dance circle, but you can enjoy just watching the dance as well. Lots of people often return to their home towns during お盆, so you may run into some old friends at the 盆踊り place.

More interesting 盆踊り may take place nearby. It’s 仮装盆踊り (かそうぼんおどり – kasou bon-odori – transformed bon dance). In most case, some 賞品(しょうひん – shouhin – prizes) are prepared like 米 (こめ – kome – rice) and 酒 (さけ – sake – Japanese rice wine, or some other alcoholic drink), etc. You can see different “people”; 侍 (さむらい – samurai), 白雪姫 (しらゆきひめ – shirayukihime – Snowwhite), 仮面ライダー (かめんライダー – kamen raidaa – literally, “masked rider,” a television program hero) and such characters from マンガ (manga) or TV. You may find the pretty princess was a man. Anyway, it’s really fun. Some of them have fancier and heavier costumes. They’re attractive and amuse the audiences, but the dancer has to struggle to continue to dance for a longer time with the tiresome costumes, lol.

Notes on Words with “お” to Indicate Politeness

As you may already know, we use words with “お” like “お盆”. Women tend to prefer to use “お” so that the expression becomes more polite. As far as thinking about お盆, generally we put “お” on more words regardless of gender, it seems.

- 盆 – お盆

- 寺 – お寺 (We don’t say “お神社” interestingly enough.)

- * 神社 – じんじゃ – jinja – shrine

- 墓 – お墓

- 経 – お経

Besides, we say “お坊さん (おぼうさん – obousan – priest)” in daily conversation instead of the word “僧侶”. The latter one is used as a written expression. The former one “お坊さん” comes from a word “坊主 (ぼうず – bouzu)”. It means the owner of the temple (“主” indicates “owner/master)” basically, but now using the word “坊主” is very rude to the priest, so you shouldn’t use it unless the priest is rude to you, lol.

Here are some everyday use words which are generally said with this polite “お” at the beginning:

- お茶 – おちゃ – o-cha – tea (generally refers to green tea)

- お金 – おかね – okane – money

- お米 – おこめ – okome – rice

- お手洗い – おてあらい – otearai – a rest room

- おじいさん – ojiisan – an old man

- おばあさん – obaasan – an old woman

- お見舞い – おみまい – omimai – visiting someone who is entering in a hospital

- お土産 – おみやげ – omiyage – souvenir(s)